This is a summary of the research from Mark Leswell, research lead at Swale Academies Trust, in the latest Impact magazine from the Chartered College of Teachers.

He makes the very helpful distinction between adaptive teaching and differentiation. Differentiation involves different resources and/or tasks for students in the same class.

Adaptive teaching monitors the needs of the child and adapts to what they can and can’t do, know and don’t know, during the lesson itself. All students cover exactly the same content as the rest of the class.

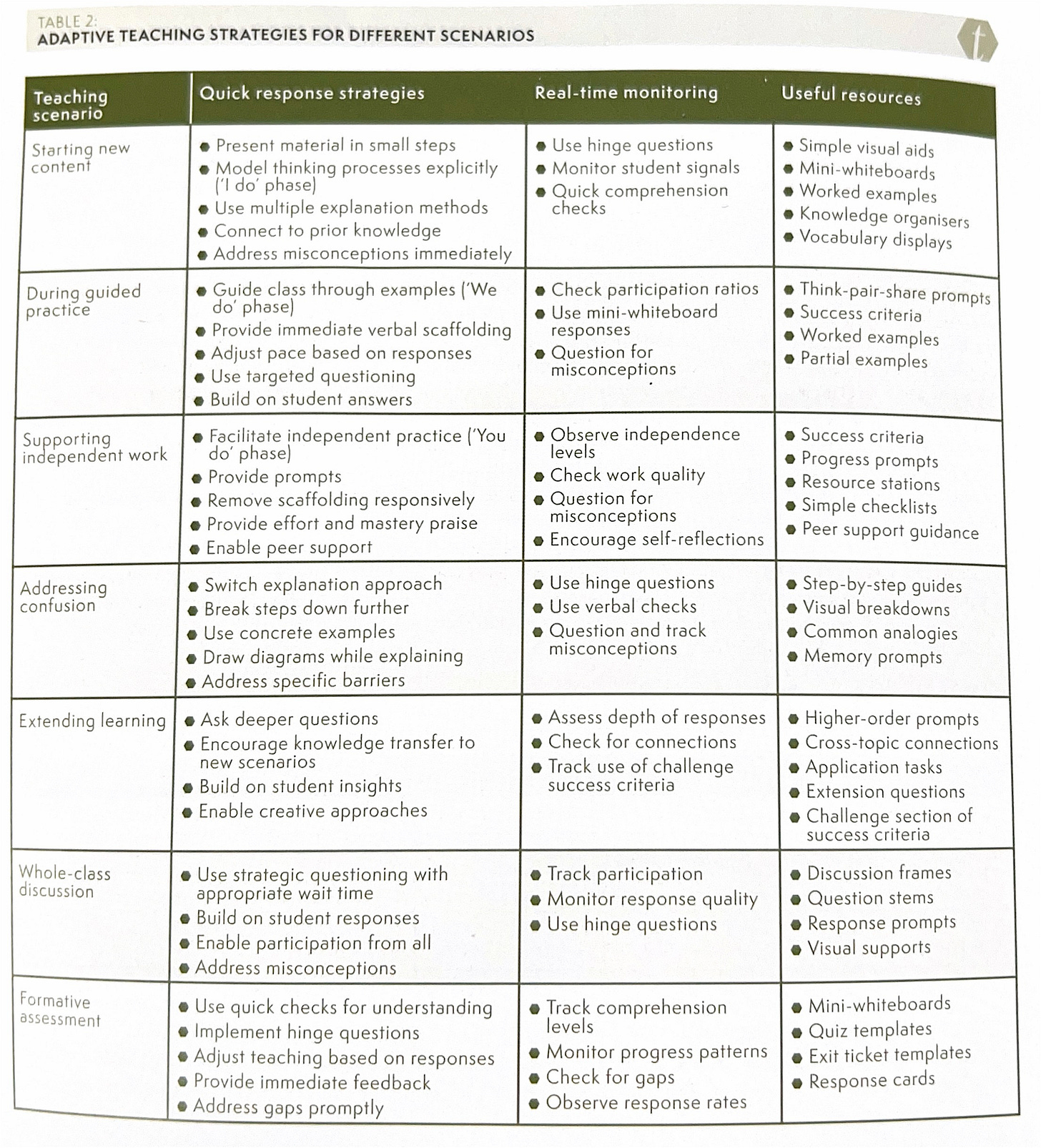

Then he gives us a table. A comprehensive table. This is seductive, and very good. Take a look.

But I want to suggest this table is also a damaging approach which is doomed to fail.

Complexity is the Enemy

First, let’s look at the headings:

‘quick response strategies’,

‘real time monitoring’ and

‘useful resources’.

The first two categories reveal a common problem. Language which requires interpretation promotes confusion, complexity and therefore causes failure.

The second failure is one which looks like strength. The table covers 7 teaching scenarios. Each scenario comprises around 12 bullet points of advice - 84 things to think about. This is everything, the A-Z, the Alpha to Omega of Adaptive Teaching! Huzzah!

But this cannot succeed. No one can hold all this in their heads.

Simplicity Saves Lives (so it will easily save your lessons)

The Checklist Manifesto tells us how to use checklists to prevent plane crashes, complications and deaths following surgery, and to pick the best companies to invest in. It is a manifesto asking us to apply the simplicity of checklists to all complex tasks.

The stories and figures are startling. You should read it.

What it tells us about checklists is that they:

A. Make steps as simple as possible

B. Exclude everything but the most critical steps

So Let’s Turn Adaptive Teaching into a Simple Checklist

Let’s rename these 3 categories with language all teachers will understand in the same way:

Lesson Plans

Teaching

Checking on Learning

(This immediately gets rid of 31 ‘useful resources’. Teachers and teams can choose to use any or all of these - but they are not essential for learning - selecting them will be nuanced, and therefore part of professional judgement).

Checklist for Lesson Planning: (This is a Read-Do Checklist)

Does the lesson begin with some retrieval which requires students to make necessary links to prior learning?

Does the lesson need spaced retrieval?

Have I made sure students copy nothing from the board?

Are the resources to read on the board exactly the same as those in booklets or textbooks in front of the students?

Does each task include a model of what good and/ or excellent looks like?

Are the explanations and instructions written on the board so students can check their understanding of them?

Are tasks broken into steps from the model rather than to the model?

Have you identified the likely misconceptions students will have, and planned accordingly?

Is there enough time in the lesson for students to practise what they’ve learned?

Why So Few?

Each of these could be unpacked with lots more detail.

For example:

The models could be faded as well.

They might involve live modelling, or a series of cloze activities focusing on key vocabulary and concepts.

They might need success criteria.

They might have key vocabulary in bold.

They might need to come from student work, rather than an examiner or teacher version.

These are all complexity. They are all for teams and teachers to develop, to make the models suit the subject and cohort. Complexity must not be part of the checklist.

The checklist does not try to be comprehensive.

It focuses on just those things which are crucial to any lesson.

Checklist for Teaching (This is a Do-Review Checklist)

Did you maximise as many retrieval questions as the time allowed (or did student writing just slow you down?)

Did you always cold call to force retrieval and check for understanding?

Do you know and use all the students’ names?

Did you sequence teaching with: I do, We do, You do or (even better) See, Try, Apply, Secure?

Did you follow your scripts for the predictable and frequent undesirable behaviours?

Did you use the visualiser or student performance to model AND sample student writing, or performance?

We could go into specific and nuanced detail about each item on the list. For example, the teaching sequence:

The differences between these two teaching sequences

How the second demands pair work and more frequent checks for understanding

Whether the ‘I do’ requires live modelling

What sort of task will provide an opportunity to ‘secure’

How much time to devote to it - etc.

All these are professional judgements and possibly subject specific. This is because they are complex.

So they don’t go in the checklist.

Checklist for Checking on Learning (This is a Do-Review Checklist)

Did you listen to ‘turn and talk’ to look for misconceptions?

Did you seek out your 4 ‘least able’ students to check for lack of understanding?

Did you circulate the room to look for misconceptions?

Did you use the visualiser (or student performance) to critique student work, usually selecting it at random?

Did you repeat this once students adjusted their work, definitely selecting it at random?

After the lesson, did you review the books / work to judge how effective the task design and learning was?

Again, this leaves a huge amount to the teacher. For example:

To circulate you must first have set up a silent solo, where students are trying something independently, or a turn and talk in pairs.

You must have decided on what to look for - misconceptions and examples of success.

You should have provided models and success criteria- but that is in planning.

You should not talk to the students, as this will lead others to go off task.

You must not answer questions for the same reason, and because you want students to apply what they have been taught.

These are skills which teachers will acquire, or argue about. The team can take their own view. They don’t all have to be non-negotiable.

A checklist does.

This is why the checklist only focuses on the most high value things. Without these things, learning will be unequivocally worse.

The Goal of the Checklist

Although the checklists are simple, they should miss nothing vital.

They have to be so easy to use that they won’t be misunderstood, or applied in different ways by different teachers, or different schools.

Gawande warns us the the very best prepared checklists will go wrong as soon as they meet real scenarios. They will need iterative refinement. Usually, they will need further simplification. And then, after that many experiments, they are ready.

(For example, ‘Did you seek out your 4 ‘least able’ students to check for lack of understanding?’ could be excessive. Why 4? What if the answer is zero, because cold calling and the use of the visualiser addresses all the most likely misconceptions and problems?)

Another goal is CPD. Each checklist tells us what teachers need to be trained on.

Then there are lesson observations or visits - it is incredibly easy for these to delve into complexity - ‘I spotted 6 things you could do differently in the lesson, and this one is the most high value.’

Is it though? It will have much more value if it is something on the checklist.

↗️ If you would like my help in experimenting with these, let me know.

↗️ Similarly, if there is something you think that a lesson must have, which is not in the checklists, let me know.